…Write Amen and share.

If you’ve been on social media for a while, you’ve surely come across “like-and-share” posts.

They come in different variations: from pictures of puppies to politicians, from sunsets to more or less sacred and religious-themed images. The latter differ slightly in their call to action, where “like” is replaced with “Amen,” but the mechanism remains the same.

The expansion of AI-generated image platforms has further weakened the already fragile state of social networks. Over the past year, we have been flooded with almost realistic images.

A keen eye and a mind trained in even the most basic source verification can immediately spot the deception. At the very least, they trigger all the warning lights on the dashboard that should be somewhere in the between of our heart and brain.

But when this dashboard resides in the gut, the eye is untrained, and the ability to filter incoming information is limited, then the flood of amen and share requests begins. It doesn’t matter if it’s a two-headed unicorn, a cat with eyes bigger than a car’s headlights, or images that even Walt Disney wouldn’t have dreamed of.

A particular category of such posts features images of lonely elderly people staring directly at the viewer. Their gaze is sad. In the foreground, on a table, there is often a cake. The accompanying text varies from:

“Today is my 98th birthday, but everyone has forgotten me.”

to

“I baked this cake for my grandson’s birthday, but no one appreciates it.”

Liking and sharing is meant, in the reader’s mind, to show appreciation and make the portrayed person feel less lonely. However, that person does not exist.

We could ask why so many people create fake images to set emotional traps for unsuspecting users. We could also wonder how, in 2025, someone still falls for chain messages.

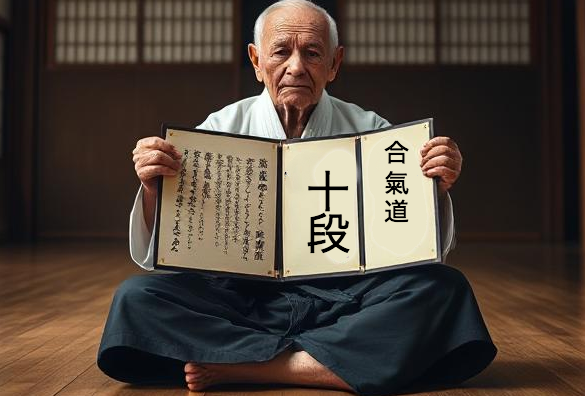

But today, we ask ourselves different questions. The starting point is this post’s cover image, which was, of course, generated with DeepAI.

Aikido seminar posters sometimes have a “type Amen and share” flavor. A sort of clan ritual, repeated cyclically within small circles, where sharing expresses the affection of a good son, and a sensei’s like on that share is the reward -the digital pat on the head from a loving father.

One day, we will reflect on the fine line between affection and dependence, between relationships and umbilical cords -but not today.

Sometimes, we see incredible ranks and qualifications from this or that organization. Outrageous dan rankings, which -within the perspective of a Japanese martial art- should make the holder something like a childhood friend of the Emperor of the Rising Sun.

But that’s not the case. And in the end, beyond the “Amen and share,” it all boils down to a few pictures of events with just a handful of participants, with rare exceptions.

Others have written, and continue to write, about ranks and qualifications. Often, between the lines, the message is: “I, the one writing and criticizing, am better than you, the reader, who holds a ridiculous fourteenth Dan. Nah nah nah.”

We are not interested in that perspective. Nor are we particularly concerned with the financial dimension behind the ranking system -though it is significant. Certainly, some administrative transparency, with clear and accessible pricing, would be beneficial. Not all organizations operate transparently.

Our reflection is that rank and qualification often serve as the only “certificate of existence” for a practitioner. And, consequently, for the instructor who becomes a teacher.

As if all the weekly work done on the tatami needed to be validated by the rank rather than the other way around.

The founders of modern Budo are probably rolling in their graves -and this would explain Japan’s constant seismic activity.

When it comes to Aikido, what remains of all those hours spent training? Certainly not a history of medals or tournament participation. Nor even internal competitions. The practitioner might sometimes say, “I’m not interested in ranks. I practice for the sake of practicing.”

Sometimes that is true. And we would all like to be so angelic and detached that we have no earthly ambitions.

Then, as the date for a test approaches and the regulations allow us to take it… the words go one way, but the body grinds itself down with training that often borders on obsessive, preparing for something that should be a celebration of a journey but instead becomes like the Christmas play we performed in elementary school.

For what?

Seeking recognition is human and necessary. Those who train children know that tests are essential and that colored belts help coregulating and unify the group within a teaching framework.

In a world increasingly fragmented -a world that produces seminar posters featuring teachers with Dans approaching infinity- it’s obvious that Aikikai plays a perceived role of standardization. Perceived doesn’t mean applied; after all, rank recognition from Tokyo happens through a vast galaxy of Aikikai-certified instructors worldwide.

The result? The fragmentation of styles, yet an equalization of ranks. So, you have acrobatic practitioners like Ryuji Shirakawa who, in Tokyo’s eyes, hold the same sixth dan as teachers who, if they tried to do what Shirakawa does, would crash in half. Conversely, Shirakawa himself would probably jump far less under the hydraulic presses of his same-ranked peers from other schools.

So, what remains? How far does the need to maintain the student-teacher relationship go, when it is often more about ego-boosting rank promotions than mutual growth and contribution to the art?

How much of our rank and qualification is about genuine achievement, and how much is about needing to prove -to ourselves and others- that we are worth something?

We believe in the need to keep Martial Arts alive and thriving. A movement that may gain prestige from international recognition but is truly valued by society for its tangible contributions -well-being, values, and social connection. Not because John Doe holds the 11th dan and Jane Doe the 30th.

In this sense, the enthusiasm of lower-ranking practitioners must be acknowledged, valued, and supported. Organizations should work toward this goal, just as experienced practitioners -and those with titles- should.

Society -or if we want to frame it in terms of impact, the audience– is won over with heart and meaningful proposals that meet its needs. We believe Martial Arts can address many needs, which dedicated practitioners and instructors, supported by institutions, can fulfill.

Perhaps one day, there will be less need to flaunt high ranks in front of empty audiences and more desire to understand how to respond to social challenges where we can -and must- make a difference.

This will only happen if we reconnect with reality. If we allow ourselves to be touched by it.

Which is the difference between actually visiting a lonely elderly person and sharing a DeepAI-generated image of one, adding “Amen,” and feeling good about our 10th dan in good intentions.